Rethinking coastal authority in Nova Scotia: We all share the coast—so let’s share its governance!

Introduction

Author: Myles De Jong. Research Assistant. International Development Studies BA program, Dalhousie University (2021-2025).

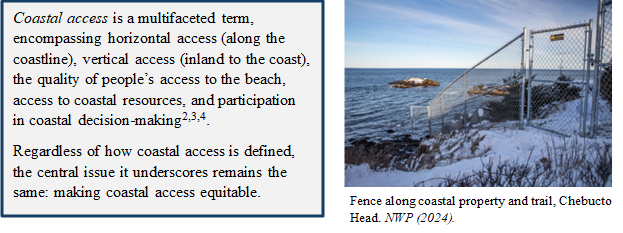

People are drawn to the coast for many reasons: natural beauty, livelihood, access to resources, trade, recreation, travel, safety, etc. Attraction to the coast has shaped settlement patterns across the world, with many communities, societies, and traditions now deeply rooted around shorelines. Consequently, coasts have become more than natural space—they are legal, cultural, and political arenas as well. They are places where multiple interests meet, where different values collide, and where critical decisions about access and exclusion are made.

Nova Scotia is no exception. Here, no one lives far from the sea. Roughly 70% of the province’s population resides in coastal communities, and even more visit the coast regularly1. Whether through walks on the beach, surfing, swimming, recreational and/or commercial fishing, cultural and traditional practices, or simply breathing in the ocean air, the coast holds meaning for a wide diversity of stakeholders. For some, it is a workplace; for others, a place of spiritual connection; for many, a site of leisure and community.

But the coast is also a space of growing conflict. Across Nova Scotia, there is a long standing history of tensions between public and private access, between economic development and environmental protection, and between the authority of governments and the rights and claims of communities and Indigenous Nations. Amid the failure to address these tensions, coastal access has become more restricted by legal ambiguity and privatization; inequities in who gets to enjoy (or control) the coast often reflect deeper, systemic disparities shaped by race, class, and colonial history—for example, the systemic disenfranchisement of African Nova Scotian’s from coastal spaces such as Africville. As climate change transforms coastal regions, those least responsible for the emissions and pollution accelerating it are often the most vulnerable to its impacts.

This three part blog series explores these complexities present along Nova Scotia’s coast by asking three important questions—questions that every coastal resident or user should consider: What is it that each of us values about the coast? Who should be responsible for coastal governance? And, what role can each of us play in shaping its future?

Coastal landowners, users, community groups, and governments all have stakes in the management of the coastline—and each bring their own contrasting economic, socio-cultural, and environmental objectives.

Authority over coastal areas can be a complex arena given the diversity of coastal stakeholders. In Nova Scotia, the existing coastal authority has failed to produce solutions to the various conflicts arising in coastal areas, sometimes to the exclusion of alternative, local visions for coastal management. This has called into question who should really be responsible for coastal governance, and which alternative governance models might be viable in Nova Scotia. Should it be the federal, provincial, and municipal governments? Should coastal policy-making be top-down, or should it foreground local communities and stakeholders voices? And, in a province which is officially and recognizably located on the ancestral and unceded territory of the Mi’kmaq people, how do we ensure Indigenous peoples have a meaningful role in such coastal conversations? i

Across the next parts of this series, we’ll explore some of the ways in which individuals and communities, near and far, have been involved in the decisions shaping their coasts—and how we might think about reshaping coastal authority altogether in the future.

If the coast is truly valuable to us all (and it is!) then each of us will have a role to play moving forward.

References

1 Ecology Action Centre. Sea-Level Rise Education & Planning. https://ecologyaction.ca/our-work/coastal-water/sea-level-rise-education-planning

2 Alterman, R., & Pellach, C. (2022). Beach Access, Property Rights, and Social-Distributive Questions: A Cross-National Legal Perspective of Fifteen Countries. Sustainability, 14(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074237

3 Twichell, J. H., Mulvaney, K. K., Merrill, N. H., & Bousquin, J. J. (2022). Geographies of Dirty Water: Landscape-Scale Inequities in Coastal Access in Rhode Island. Frontiers in Marine Science, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.760684

4 Mafumbu, L., Zhou, L., & Kalumba, A. M. (2022). Assessing Public Perceptions on Coastal Access -Community Profile: A Case Study of Ngqushwa Local Municipality, South Africa. Sustainability, 14(21). https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113994

5 Warrior, M., Fanning, L., & Metaxas, A. (2022). Indigenous peoples and marine protected area governance: A Mi’kmaq and Atlantic Canada case study. FACETS, 7, 1298–1327. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2021-0128

This publication is the result of a collaboration between the Ecology Action Centre and Climate Justice: Values and Vulnerability